Useful links: |

Woodward Family Tree by Graham Woodward |

Guide to Church Baptisms |

|

Parish records started in 1538, but only about 800 registers have survived from this date. The records began with the use of single sheets of paper, but from 1598 books were introduced under an Order made by Queen Elizabeth I. Only the paper entries from 1558 onwards (the start of Elizabeth's reign) were copied into the new books, which means that in many parishes the records for the period 1538 to 1558 have been lost. |

In some parishes the Bishop's copy was the original record with the parish record being updated later. In other parishes it was the other way around; it was down to the individual clergy. Making up the record at a later date naturally resulted in errors and omissions. For this reason if you can't find a record in the parish record you should always check the Bishop's Transcript as well.

In order to know where to look in the records and understand what the records tell us, we need to have some understanding of the scale of English society, the way people lived and how their need to find work, even into old age, affected where their children were baptised.

Background

The Domesday Book tells us that in 1087 AD there were 2053 churches in England and 268,125 rural households. The best estimates based on the book put the population of England in 1087 at just under 1.5 million. The book shows that at the time of the Conquest, 89% of the population lived in the rural environment whereas by the year 2000 the exact opposite was the case (89% lived in urban areas). The coming of the railways in the 1840s meant that for the first time families could move considerable distances to find work and the census returns from 1851 onwards show this migration by including the county or place of birth.

One thing to bear in mind is that children were not always baptised in the same village or town where they were born. Most first born children were baptised in the mother's home parish, but second and subsequent children were usually christened in the parish in which the parents lived. Also, the average age at baptism increased from one week old in the middle of the 17th century to one month old by the end of the 19th century as child mortality rates reduced.

In most families, the fertility period of a woman was up to age 41 or 42. Very rare cases of women aged 48 having children have been found, but women who had their first child in their mid thirties onwards were at far greater risk of death in childbirth, and if you cannot find any more children baptised to a couple it is worth looking for a death of the mother soon after a baptism of the last child.

The average number of children born to each family (called the Total Fertility Rate) was determined by many factors, and heavily influenced by the average age of marriage for women. In the 1700s, the average age at marriage for labouring class women was 26 years, resulting in a total fertility rate of 5 (ie. five children born during a 16 year fertility period up to age 42). Clearly some couples had much larger families, but five is the average for the 18th century, with a small increase in the 19th century due to the better survival rate of children, although not in some cities such as London. Family size was also affected by average life expectancy of the parents, particularly the husband. In 1750 this was age 37 years for men, rising to the low forties after 1800 where it stayed until the late 19th century. (Today, 2020, average life expectancy in the UK is 81 years and the total fertility rate is 1.79.)

So, when looking for children born to a particular couple all these factors must be considered, and don't dismiss children born to what appears to be an older woman if all the other indicators suggest he/she is from the same family.

Early baptism records

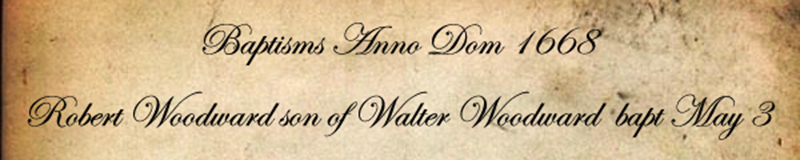

Records from the 16th, 17th and early 18th century often include only the child's name and the father's name. A typical example would be:

|

The age of a person being baptised wasn't normally shown until 1813 onwards when George Rose's Act compelled vicars to use a new record book. Adults were sometimes baptised when they joined the church for the first time or before getting married, as some vicars insisted that they be 'brought into the church' before he would marry them.

From the late 16th century onwards, a number of Protestant nonconformist churches began to emerge. These would often conduct their own baptisms, usually in secret. In addition, several Catholic priests performed baptisms in secret. Nonconformity was attacked by both the established church and the state until the Toleration Act of 1688 brought much of the persecution to an end. Nonconformity grew steadily and an increasing number of baptisms were carried out in nonconformist chapels and recorded in their registers. Non-conformist registers are only common after 1780 and relate to about 6% of all baptisms.

In the 1700s mobility was more common than we realise, especially for agricultural labourers. Many worked as journeymen - taken on for seasonal work, then moving to another village or estate later when the work dried up. Movement was usually contained within a twenty mile radius of a person's home or place of birth, although the building of the canals in the late 1700s and the railways in the mid 1800s opened up greater opportunities to find work further afield. Seasonal mobility affected where the children of a family were born and baptised and can result in records being overlooked on the basis that they are too far from 'home'.

Illegitimacy (birth to an unmarried mother) reached 5% in 1590, 6% by 1800 and 7% by 1845. Today it is 40%. Parish record entries of illegitimate children normally name only the mother. The name of the father is sometimes added (as required by an Act of 1634) but not always, as often the mother refused to give the name. In most cases, before the advent of Social Security, it was the parish that had to support a woman and child who had no husband, and for this reason in 1733 the Bastardy Act ordered that fathers of illegitimate children should be committed to jail unless they made arrangements to indemnify the parish for the upkeep of the child. In most cases this forced men to marry the expectant mother. This may have been one reason why many women refused to name the father.

Often vicars refused to baptise illegitimate children, but in the 18th and 19th centuries those that were baptised were usually given the mother's surname. Illegitimacy may explain why you can't later find a baptism for an ancestor that you have a marriage record for. In some cases the father's surname was used as a middle christian name. One example on a tree of mine is a William Herbert Smith Baker born in 1857 - his father may have been named Smith. In some records the child's illegitimacy was shown by the addition of the word 'base'.

Missing records

Many baptism records were lost during the English civil war. Between 1640 and 1660 it is estimated that one-sixth of all baptisms are missing from the records and many children were not baptised during this period, although a flood of baptisms took place after the Restoration in 1660 which can now play havoc with family research. Additionally, records were lost through negligence on the part of the vicar, who failed to keep the books in good condition. Ironically many clergy changed the old wooden church chests for ones made of metal in the belief that they would better protect the contents, but as metal doesn't 'breath' like wood they retained the damp and the records were even more prone to damage.

The Parochial Registers and Records Measure 1978, required that from 1 January 1979 a new register book of public or private baptisms and burials be issued to all parishes and all old books be closed. All parish registers starting 150 or more years earlier (with the exception of marriage registers from July 1837 onwards) were to be deposited with the Diocesan Record Office. In most cases the records were later moved to the County Record Offices. One original register I looked at for Morton Bagot in Warwickshire, a very small hamlet, had been started in 1665. The church used the same book until 1813 when new printed registers were introduced.

Infant mortality

Between 1700 and 1800, 5% of children died within the first few days of birth and 20% died before age 10 years. Many infants who died at birth or shortly afterwards were not baptised which may account for a long gap in a family tree. In wealthy families, some children were baptised quickly if they thought the child would die, as this then allowed for a formal church burial. A gap in the regular two to three year birth cycle may also mean a stillbirth or miscarriage, (generally accepted as being before 24 weeks).

Two children of the same forename shown as being baptised to the same parents usually means that the first child died. However, because family size was much larger than today (the average size in 1850 was six children over a 15 year period, although many families had 10 children) the first child may well have grown up and moved away by the time the last child was born, so using the same forename for two sons wasn't a problem. Also, wives of second marriages sometimes called their children by the same christian name as an older child from the husband's first marriage. However, these situations are quite rare. Whenever you do find this situation it is advisable to first check for a burial.

Dade registers

From around 1770 to the early 1800s many parishes, particularly in Yorkshire, adopted a style of register promoted by the Archbishop of York based on the ideas of William Dade, a Yorkshire clergyman. Dade registers for baptism entries usually record not only the name of the subject but also of the parents, including the mother's maiden name, and of the subject's grandparents, at least in the male line. Dade registers are therefore some of the most valuable records available. The introduction of printed forms in 1813 brought their use to an end.

Rose's Act 1812

George Rose's Act 1812 decreed that church incumbents were to keep two specially printed registers to record baptisms and burials separately. These were separate from the marriage register standardised by Hardwick's Act 1753. From 1813 the new books had printed columns and these are much easier to read. The new entries contained the following information:

- date baptised and register entry number

- child's Christian name

- parents names

- abobe (address)

- trade or profession

- name of person performing the ceremony.

Sometimes notes were added such as, "illegitimate son of Alice", and no father's name.

Civil Registration of Births 1837

The introduction of civil registration in 1837 had little effect on church baptisms as the act concentrated on births not the religious event known as baptism. Legally, all births must be registered within 42 days of the event, and it is a widespread misconception that many births were not registered under the new system. The true position is that the non-registration rate was very low, and that a later act in 1875 only changed who was responsible for registration. It is also the case is that after the Second World War (1939-45) many children were not baptised, and the only record available is the civil registration of their birth.

|

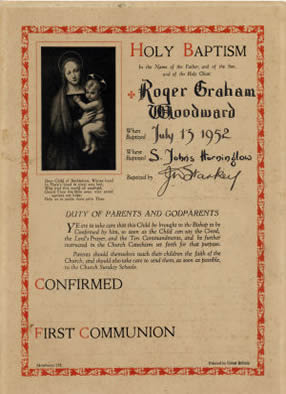

Baptism Certificates

Children who were baptised were sometimes given a Baptism Certificate. A typical example from the 1950s is shown on the left. They were used by most Christian denominations, but were not to any standard design. These certificates were usually issued by the vicar after the ceremony, but today they are even available as an MS Word template and can be printed by anyone, although to be authentic they must still be signed by the vicar. Baptism Certificates usually include information such as the individuals name, the date, and the church in which the ceremony took place. Some certificates also contain the age of the child at the time of the baptism, and in many cases this was the only place that the age was formally recorded. |

The International Genealogical Index (IGI)

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the Mormon Church) has compiled the International Genealogical Index (IGI), an index of baptisms, marriages and deaths taken from information contained in various sources, including the parish records. The index contains over 1 billion records from between 1550 - 1900. At one time, copies were available on CD-ROM in most big libraries and county record offices, but the index can now be accessed online (a link is available at the top of this web page).

The index is a wonderful aid to getting started. Using the search facility online you can look for baptisms in a wide range of parishes, based on the person's name. Using the Batch Number system, you can also discover all children of a single family that were baptised in a specific parish.

Beware: the IGI is only an index. Any database the size of the IGI will have errors and omissions, and all records must be verified from other (original) sources. However, the index will help you focus on which records to look at. In 2008, the Catholic Church blocked access to their records and some Jewish records have been removed, but genealogists still owe a great debt to the Mormon's for this wonderful resource.

Ancestry online

Ancestry has made researching our family history much easier, as many parish records and census returns are now available online and indexed by name. It is a great resource, with the Ancestry UK section containing over 1 billion family history records, and is well worth the subscription fee. In Ancestry, if you search the Card Catalogue and enter your chosen county, you can then see a list of all parish records available for that county. By selecting the parish you can trawl through the record itself rather than using the name index, which is very useful if you do not have much information about the person you are looking for.

If you cannot find an event on Ancestry it does not mean that it didn't happen. In many cases a visit to the local records office to view the register may still be necessary.

Important point about the calendar

Up until 1752 in England, new years day was celebrated on 25th March not 1st January; eg. December 1750 would be followed immediately by January 1750. It is therefore easy to dismiss baptism records because they seem to be at the wrong time.

An example of how this can lead to a baptism being ignored would be where a couple were married in May 1750 and their first child was born nine months later, ie. February 1750. The baptism would probably be in early March 1750, (what we would now call March 1751). On first sight the baptism would be ignored as being nearly three months before the parents were married and in the belief that the child belonged to another couple with the same christian names, when in fact it was perfectly in order.

Compiled by Graham Woodward, Nottingham, England (UK).